by Brian Shilhavy

Editor, Health Impact News

It has been a year and a half now since the first Large Language Model (LLM) AI app was introduced to the public in November of 2022, with the release of Microsoft’s ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI.

Google, Elon Musk, and many others have also now developed or are in the process of developing their own versions of these AI programs, but after 18 months now, the #1 problem for these LLM AI programs remains the fact that they still lie and make stuff up when asked questions too difficult for them to answer.

It is called “hallucination” in the tech world, and while there was great hope when Microsoft introduced the first version of this class of AI back in 2022 that it would soon render accurate results, that accuracy remains illusive, as they continue to “hallucinate.”

Here is a report that was just published today, May 6, 2024:

Large Language Model (LLM) adoption is reaching another level in 2024. As Valuates reports, the LLM market was valued at 10.5 Billion USD in 2022 and is anticipated to hit 40.8 Billion USD by 2029, with a staggering Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 21.4%.

Imagine a machine so native to language that it can write poems, translate languages, and answer your questions in captivating detail. LLMs are doing just that, rapidly transforming fields like communication, education, and creative expression. Yet, amidst their brilliance lies a hidden vulnerability, the whisper of hallucination.

These AI models can sometimes invent facts, fabricate stories, or simply get things wrong.

These hallucinations might seem harmless at first glance – a sprinkle of fiction in a poem, a mistranslated phrase. But the consequences can be real, with misleading information, biased outputs, and even eroded trust in technology.

So, it becomes crucial to ask, how can we detect and mitigate these hallucinations, ensuring LLMs speak truth to power, not fantastical fabrications? (Full article.)

Many are beginning to understand this limitation in LLM AI, and are realizing that there are no real solutions to this problem, because it is an inherent limitation of artificial computer-based “intelligence.”

A synonym of the word “artificial” is “fake”, or “not real.” Instead of referring to this kind of computer language as AI, we would probably be more accurate in just calling it FI, Fake Intelligence.

Kyle Wiggers, writing for Tech Crunch, reported on the failures of some of these recent attempts to cure the hallucinations of LLM AI a few days ago.

Why RAG won’t solve generative AI’s hallucination problem

Hallucinations — the lies generative AI models tell, basically — are a big problem for businesses looking to integrate the technology into their operations.

Because models have no real intelligence and are simply predicting words, images, speech, music and other data according to a private schema, they sometimes get it wrong. Very wrong. In a recent piece in The Wall Street Journal, a source recounts an instance where Microsoft’s generative AI invented meeting attendees and implied that conference calls were about subjects that weren’t actually discussed on the call.

As I wrote a while ago, hallucinations may be an unsolvable problem with today’s transformer-based model architectures. (Full article.)

Devin Coldewey, also writing for Tech Crunch, published an excellent piece last month that describes this huge problem of hallucinating inherent in AI LLMs:

The Great Pretender

AI doesn’t know the answer, and it hasn’t learned how to care.

There is a good reason not to trust what today’s AI constructs tell you, and it has nothing to do with the fundamental nature of intelligence or humanity, with Wittgensteinian concepts of language representation, or even disinfo in the dataset.

All that matters is that these systems do not distinguish between something that is correct and something that looks correct.

Once you understand that the AI considers these things more or less interchangeable, everything makes a lot more sense.

Now, I don’t mean to short circuit any of the fascinating and wide-ranging discussions about this happening continually across every form of media and conversation. We have everyone from philosophers and linguists to engineers and hackers to bartenders and firefighters questioning and debating what “intelligence” and “language” truly are, and whether something like ChatGPT possesses them.

This is amazing! And I’ve learned a lot already as some of the smartest people in this space enjoy their moment in the sun, while from the mouths of comparative babes come fresh new perspectives.

But at the same time, it’s a lot to sort through over a beer or coffee when someone asks “what about all this GPT stuff, kind of scary how smart AI is getting, right?” Where do you start — with Aristotle, the mechanical Turk, the perceptron or “Attention is all you need”?

During one of these chats I hit on a simple approach that I’ve found helps people get why these systems can be both really cool and also totally untrustable, while subtracting not at all from their usefulness in some domains and the amazing conversations being had around them. I thought I’d share it in case you find the perspective useful when talking about this with other curious, skeptical people who nevertheless don’t want to hear about vectors or matrices.

There are only three things to understand, which lead to a natural conclusion:

- These models are created by having them observe the relationships between words and sentences and so on in an enormous dataset of text, then build their own internal statistical map of how all these millions and millions of words and concepts are associated and correlated. No one has said, this is a noun, this is a verb, this is a recipe, this is a rhetorical device; but these are things that show up naturally in patterns of usage.

- These models are not specifically taught how to answer questions, in contrast to the familiar software companies like Google and Apple have been calling AI for the last decade. Those are basically Mad Libs with the blanks leading to APIs: Every question is either accounted for or produces a generic response. With large language models the question is just a series of words like any other.

- These models have a fundamental expressive quality of “confidence” in their responses. In a simple example of a cat recognition AI, it would go from 0, meaning completely sure that’s not a cat, to 100, meaning absolutely sure that’s a cat. You can tell it to say “yes, it’s a cat” if it’s at a confidence of 85, or 90, whatever produces your preferred response metric.

So given what we know about how the model works, here’s the crucial question: What is it confident about? It doesn’t know what a cat or a question is, only statistical relationships found between data nodes in a training set. A minor tweak would have the cat detector equally confident the picture showed a cow, or the sky, or a still life painting. The model can’t be confident in its own “knowledge” because it has no way of actually evaluating the content of the data it has been trained on.

The AI is expressing how sure it is that its answer appears correct to the user.

This is true of the cat detector, and it is true of GPT-4 — the difference is a matter of the length and complexity of the output. The AI cannot distinguish between a right and wrong answer — it only can make a prediction of how likely a series of words is to be accepted as correct. That is why it must be considered the world’s most comprehensively informed bullshitter rather than an authority on any subject. It doesn’t even know it’s bullshitting you — it has been trained to produce a response that statistically resembles a correct answer, and it will say anything to improve that resemblance.

The AI doesn’t know the answer to any question, because it doesn’t understand the question. It doesn’t know what questions are.

It doesn’t “know” anything! The answer follows the question because, extrapolating from its statistical analysis, that series of words is the most likely to follow the previous series of words. Whether those words refer to real places, people, locations, etc. is not material — only that they are like real ones.

It’s the same reason AI can produce a Monet-like painting that isn’t a Monet — all that matters is it has all the characteristics that cause people to identify a piece of artwork as his. (Full article.)

“AI” was the new buzz word for 2023 where everything and anything related to computer code was being called “AI” as investors were literally throwing $billions into this “new” technology.

But when you actually examine it, it really is not that new at all.

Most people are familiar with Apple’s female voice “Siri” or Amazon.com’s female voice “Alexa” that responds to spoken language and returns a response. This is “AI” and has been around for over a decade.

What’s “new” with “generative AI” like the new LLM applications, is the power and energy to calculate responses has greatly been expanded to make it appear as if the computer is talking back with you as it rapidly produces text.

But these LLM’s don’t actually create anything new. They take existing data that has been fed to them, and can now rapidly calculate that data at speeds so fast that it makes the older technology that powers programs like Siri and Alexa seem to be babies who have not yet learned how to talk like adults.

But it is still limited to the amount, and the accuracy, of the data it is trained on. It might be able to “create” new language structures by manipulating the data, but it cannot create the data itself.

Another way to look at it, would be to observe that what it is doing in the real world is making humans better liars, by not accurately representing the core data.

This enhanced ability to lie really struck me recently when watching a commercial for the new Google Phones:

Here Google is clearly teaching people how to deceive people and lie about the actual data that a Google phone captures by using “AI”, as in photographs.

Lying and deceiving people sells, while the truth most often does not, and when the public watches a commercial like this for Google’s latest phone, the reaction, I am sure, among most, is that this is really great stuff, as our society has now conditioned us to believe that lying and deceiving people is OK in most situations.

In the world of Big Tech today, “data” is the new currency, and “Dataism” is the new religion.

If you have not read the article I published last year by Zechariah Lynch who astutely observes where all of this is going, or at least where the Technocrats want it to go, please give this a read and educate yourself:

“Dataism” is the New Religion of AI and Transhumanism: Those Who Own and Control the Data Control Life

As I mentioned in a recent article, those who are training these LLM models are starting to panic because they are “running out of data.”

This brings up another serious flaw with the new LLM AI models: everything they generate from existing data is data that was created by someone and is cataloged on the Internet, which means that whatever is generated by this AI, whether it is accurate or not, is THEFT!

This technology is advancing so rapidly that the legal implications are not fully litigated yet, but I decided early last year that I would not use AI to help me generate any text or graphics, because I have no desire to be a thief and steal other people’s work.

When I write an article today, as I have done for decades, I try my best to cite the original source of everything I use in my articles, giving credit where credit is due.

LLM AI generally does not do this. AI has no soul and no concept of right or wrong. It simply follows a script, computer scripts programmed by humans that are called algorithms.

Currently data can only be input to computers in limited ways: by text, by sound via microphones, and by images and moving images via a camera.

This limitation alone assures that computers, or AI programs, will never replace humans, who can input data in more than just these three ways, and include the senses as well, such as smell, taste, etc., which as of yet cannot be translated to digital data.

But the greatest data collection abilities that humans have is the non-physical, or “meta-physical”.

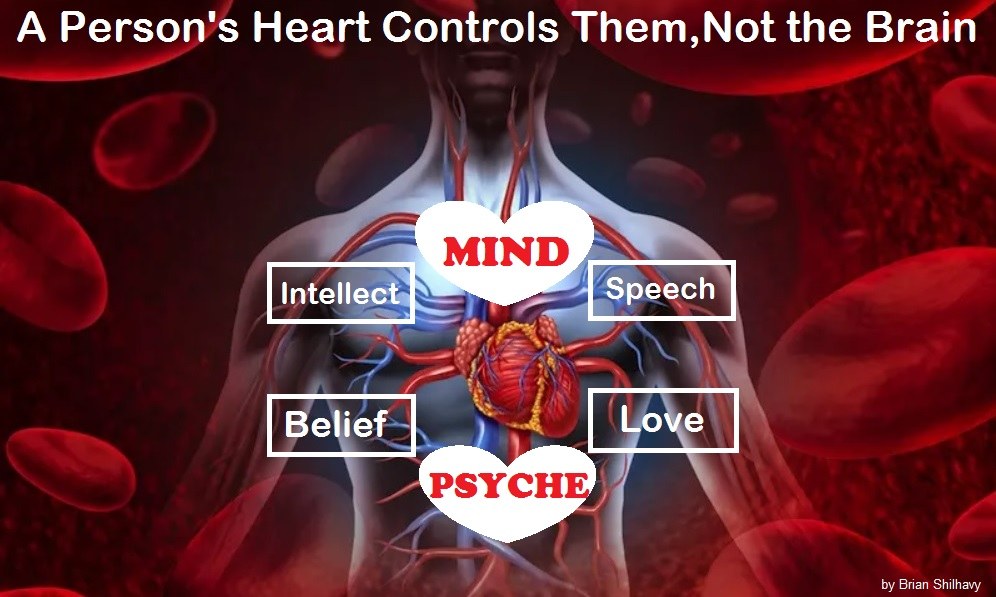

Hundreds of years of Darwinian biological evolution theory has taught most westerners that our brain is the center of our consciousness, whereas the ancients have always believed, for thousands of years, that our heart is the center of our consciousness.

This is the view of the biblical ancient writings, as well as others. See:

The Brain Myth: Your Intellect and Thoughts Originate in Your Heart, Not Your Brain

And there is nothing in “modern science” that disproves this belief.

As I wrote last year on this topic, if anything, there is scientific evidence that confirms the central place of our heart in our life.

This evidence comes from stories of people who receive heart transplants, and then find themselves thinking about and remembering things that the person who donated their heart experienced before they died, even though the recipient of the new heart never knew the donor.

Nobody has ever received a transplant of someone else’s brain.

A 2020 study published in Medical Hypotheses actually addresses this issue.

Abstract

Personality changes following heart transplantation, which have been reported for decades, include accounts of recipients acquiring the personality characteristics of their donor. Four categories of personality changes are discussed in this article: (1) changes in preferences, (2) alterations in emotions/temperament, (3) modifications of identity, and (4) memories from the donor’s life. The acquisition of donor personality characteristics by recipients following heart transplantation is hypothesized to occur via the transfer of cellular memory, and four types of cellular memory are presented: (1) epigenetic memory, (2) DNA memory, (3) RNA memory, and (4) protein memory. Other possibilities, such as the transfer of memory via intracardiac neurological memory and energetic memory, are discussed as well. Implications for the future of heart transplantation are explored including the importance of reexamining our current definition of death, studying how the transfer of memories might affect the integration of a donated heart, determining whether memories can be transferred via the transplantation of other organs, and investigating which types of information can be transferred via heart transplantation. Further research is recommended. (Source.)

See Also:

Memory transference in organ transplant recipients

10 Organ Recipients Who Took on the Traits of Their Donors

Excerpt:

Claire Sylvia Has Strange Cravings and Dreams – New England

Not only did the heart and lung transplant that 47-year-old Claire Sylvia received save her life, but it also made her the first person in New England to undergo the process. She’s also convinced that in addition to vital organs, she received some of her donor’s tastes as if his memories were locked into his heart and lungs and consequently are now flowing in her body.

She told a reporter that when she was asked what she wanted to do first after the operation, she said that she was “dying for a beer right now.” This was strange to Claire, as she’d never enjoyed beer in the slightest before. Over the coming days, she also found that she was experiencing cravings for foods that she’d never liked or even eaten before, such as green peppers, Snickers chocolate bars, and strangely, McDonald’s Chicken McNuggets, something which she’d never had a desire to eat.

She also began to experience strange dreams. She would see a thin, young man who she believed was called Tim. Specifically, she had the words “Tim L” in her mind when she had the dreams. By searching through local obituaries of the days leading up to the day of her transplant, she came across Timothy Lamirande.

Timothy Lamirande was 18 years old when he died in a motorcycle accident on the same day as Claire’s transplant. He had been on his way home from a local McDonalds restaurant. A bag of Chicken McNuggets was found in his jacket pocket when doctors removed his clothing in a desperate attempt to save his life.

She managed to track down Tim’s family, whom she hadn’t met before, and they confirmed to her that the cravings she was having were indeed all for foods that Tim had enjoyed very much, beer and all. She has remained in touch with Tim’s family ever since. (Full article.)

Here is a video that ABC News published 8 years ago about a baby who was born with virtually no brain, and how doctors told the parents to abort him, because he had no chance to live with no brain.

But the parents did not take their medical advice, and their baby, Jaxon, lived for almost 6 years without a brain. The reason he was able to do so, in defiance of doctors and medicine, is because his consciousness was in his heart, which was fine, and not his brain.

AI and computers, run on electricity, will NEVER replace humans who are run on blood, pumped by our hearts.

More Reading on AI:

The 75-Year History of Failures with “Artificial Intelligence” and $BILLIONS Lost Investing in Science Fiction for the Real World

“Data” unavailable to computers:

No, we speak of God’s secret wisdom, a wisdom that has been hidden and that God destined for our glory before time began. None of the rulers of this age understood it, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.

However, as it is written: “No eye has seen, no ear has heard, no mind has conceived what God has prepared for those who love him”—but God has revealed it to us by his Spirit.

The Spirit searches all things, even the deep things of God.

For who among men knows the thoughts of a man except the man’s spirit within him?

In the same way no one knows the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God.

We have not received the spirit of the world but the Spirit who is from God, that we may understand what God has freely given us. (1 Corinthians 2:7-12)

Comment on this article at HealthImpactNews.com.